Note: This was originally published on January 24, 2020.

Geoffrey James recently published opinion articles proposing that PowerPoint use should be rejected. In It's 2020. Why Are You Still Using PowerPoint? he argues that PowerPoint is ineffective and hated by everyone. In the article Jeff Bezos, Mark Cuban, and Tony Robbins Don't PowerPoint. They Do This Instead he recommends presentation approaches that deliberately avoid PowerPoint. This negative opinion of PowerPoint is similar to numerous critics such as Edward Tufte and many others.

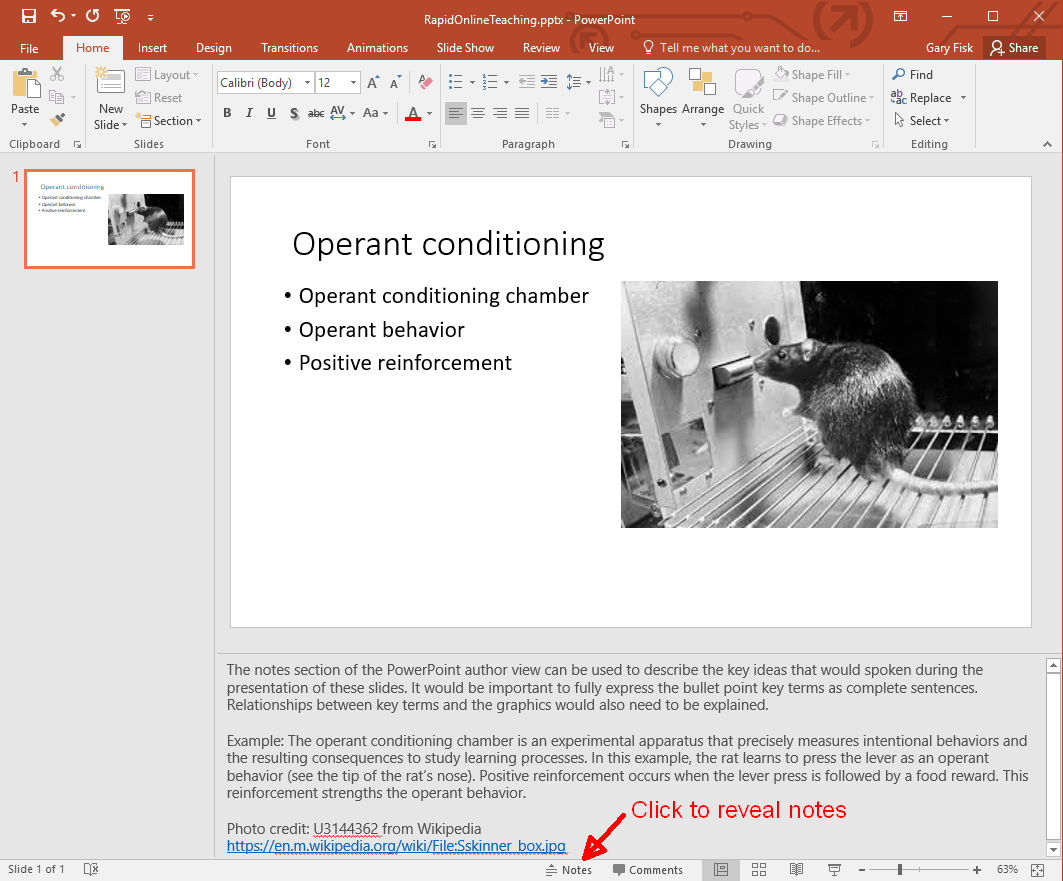

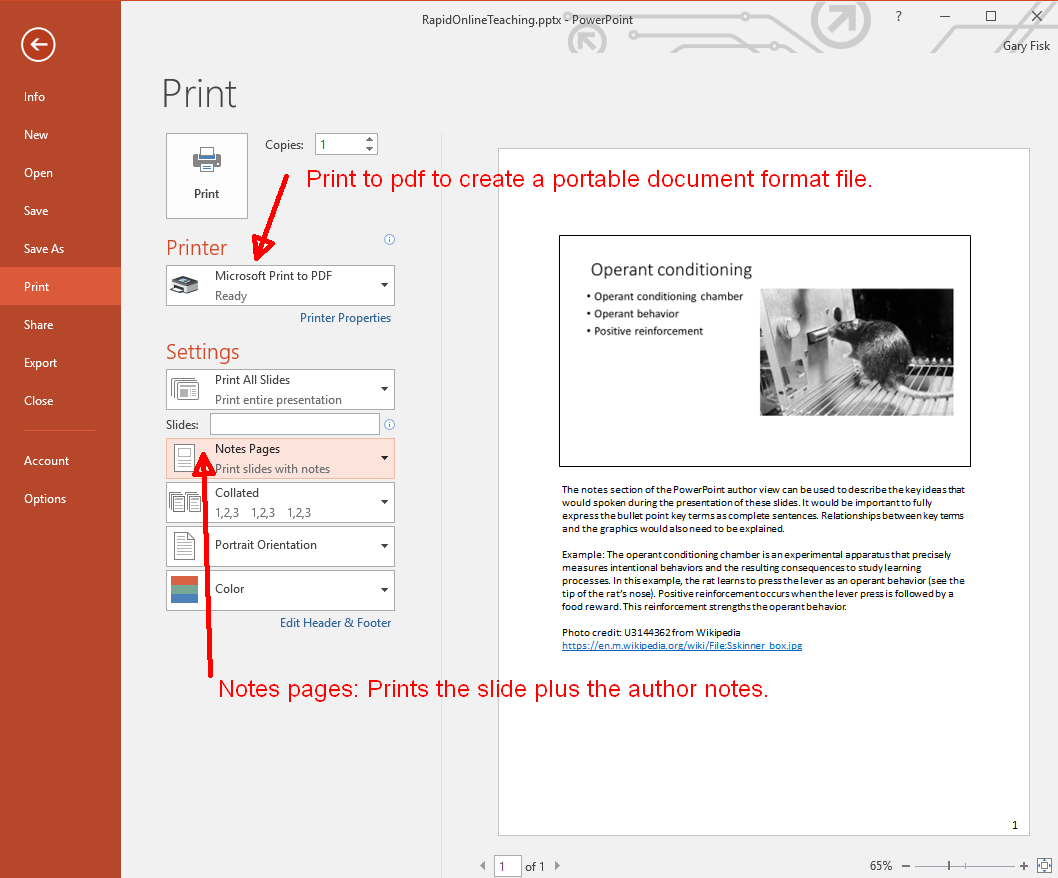

The issues raised by PowerPoint critics should always be seriously considered. These are very real problems. James is correct in saying that media comparisons studies (i.e., PowerPoint vs. chalkboards and other technologies) done by educators and cognitive psychologists don't show much of a learning boost from PowerPoint (see my book for a thorough review). In addition, it is well-known (to cognitive psychologists anyway) that the text on a slide can compete with the words that the presenter is speaking, thereby creating a divided attention problem. What is more important to the audience, the text on the slide or the words the speaker is saying? This competition between displayed text and spoken words can detract from a speaker's message.

Although important points are raised, I disagree with this excessively negative view of PowerPoint. Here are a couple of counterpoints to consider.

There is an extensive literature in educational psychology showing that graphic images can foster the understanding of complex topics. Dual coding theories suggest that the combination of words plus instructional images can have a synergistic effect that promote learning. This is particularly true in the STEM areas, where understanding topics like "How does the heart work?" require words like key terms plus a mental visualization of the processes. There is still research work to be done in this area. It's not fully understood why graphic images are sometimes helpful for learning but sometimes are ineffective. Similarly, it's not well understood why some images promote audience interest while others may be distractions that harm a presentation.

A second point to consider is that PowerPoint is a technology. When bad presentations occur, it's the presenter who should be blamed, not the technology. Most people receive little to no training in how to give presentations. Their only training may have been a speech class in high school or college. The average person rarely gives presentations, so they have few opportunities to improve their presentation skills. Finally, most people are anxious or even terrified of speaking in public. For these people reading text off a PowerPoint slide is the easiest way through a situation that they dread and are poorly prepared to perform.

An analogy is helpful for illustrating this point. Let's imagine an artist who spends a lot of money to get the best possible paints, brushes, studio space, and other equipment. However, this artist has no training, rarely paints, and didn't have much artistic talent to begin with. They maybe even dread the painting process! The end result will be mediocre to poor art. It would be a logical error to blame the brushes and other equipment for this artistic failure. The person is at fault here. This judgment seems reasonable for art, but when it comes to presentations somehow the technology receives most of the blame rather than the presenter. (It's important to note that this analogy isn't really mine. The artist and musician David Byrne has made a similar comparison between art and PowerPoint presentations.)

In closing, I think Geoffrey James and similar critics are being excessively negative. PowerPoint adds value to a presentation when it is carefully designed to support a speaker's message. Furthermore, the proposed solutions like "go entirely slide-less" are unrealistic for the average presenter. It would be more helpful to follow-up known PowerPoint presentation problems with constructive solutions. What we really need is more training in how to give a good presentation and a better understanding of how PowerPoint works (or doesn't work) for an audience rather than simple suggestions to completely drop the use of PowerPoint.

(If you're interested in dark adaptation, here is the

(If you're interested in dark adaptation, here is the