Note: This was first published on May 7, 2020.

The news lately has been full of statistical concepts relating to the COVID-19 virus crisis. "Flattening the curve" has become a commonly used term. Critical decisions such as reopening businesses are being based upon testing results. Here's my take on these virus-related statistics based upon my nearly 20 years of teaching introductory-level statistics classes.

Statistics for small groups is pretty straight-forward: Test everyone and then calculate averages, make graphs, or do other summary statistics. This is called descriptive statistics. The simple goal is summarizing or describing what a group is like. An example might be a teacher summarizing the results of an exam by calculating a class average. This use of statistics is fairly simple to understand and interpret.

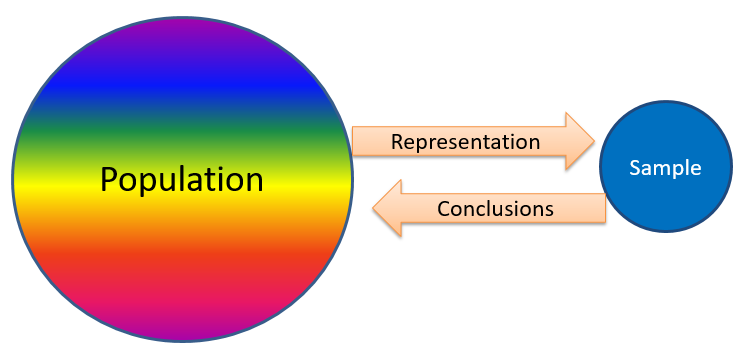

A more difficult situation occurs when we study small groups of people (samples) that are drawn from much larger groups of people (populations). This is called inferential statistics. We usually study samples of people because most populations are simply too large to study. For the virus situation, it would be impossible to simultaneously test 300+ million people in the United States at the same time.

The above diagram illustrates this inferential statistics process. The large population (left circle) represents everyone in our society who may or may not have the virus. This is too many people to test, so we must settle for testing smaller samples (right circle). The conclusions from this sample group are presumably true for the population.

Studying samples gets around the practical problem of studying millions of people. However, the risk is that the conclusions may be inaccurate. A crucial feature is that the sample must accurately represent the population, like a miniature version of the population. In the above diagram, the population has many colors to represent the variability of people in the population.

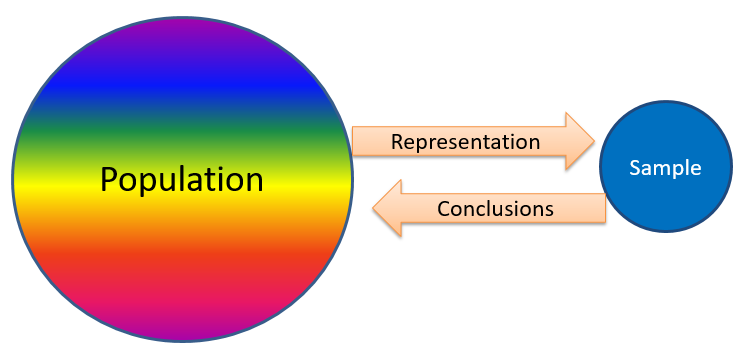

This second diagram represents a biased sample. It illustrates how a small sample might be quite different from the population that it was drawn from. The population has many colors, but the sample is only blue. Any conclusions made from this sample might be quite misleading because of the biased sample.

We are seeing some of these sampling limitations in the current COVID-19 virus crisis. The key question is how many people have been infected? The official numbers come from small samples due to the limited availability of testing kits. Only the sickest patients are being tested in many parts of the country. There is also the issue of false negatives: people who are disease carriers yet pass a virus test without showing signs of the disease.

Taken together, these issues suggest that the official numbers are underestimated. The true number of people who carry or die from the virus is likely higher than the official numbers. We don't really know for certain how many people have the virus in the population. It's a fuzzy picture of what's actually occurring. This statistical perspective is important to keep in mind when you see news stories about the number of people who have been infected.

Update: July 2, 2020

Several studies have been published since this blog post about the underestimation of cases. From Weinberger et al. (2020): "Official tallies of deaths due to COVID-19 underestimate the full increase in deaths associated with the pandemic in many states." The New York Times also has this nice summary of research from the CDC: "The number of coronavirus infections in many parts of the United States is more than 10 times higher than the reported rate, according to data released on Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention."

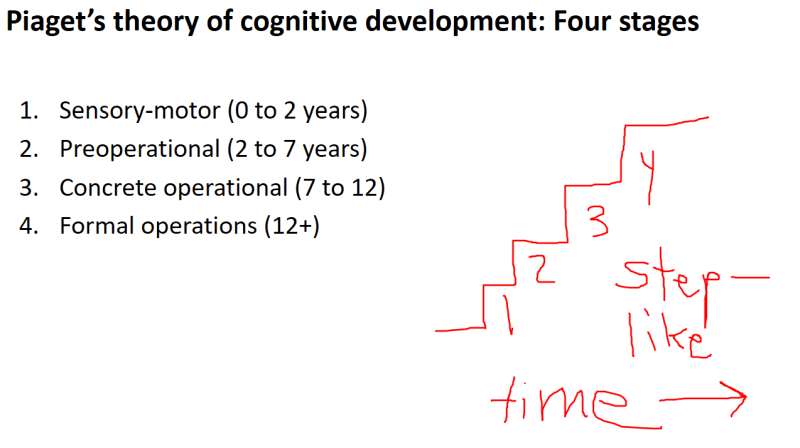

The annotated slides can be saved, exported to a pdf file, and shared with students.

The annotated slides can be saved, exported to a pdf file, and shared with students.